All over the world, natural daylight has been exchanged for artificial light forms at the expense of our health and even productivity. With better building design, though, we can reclaim the daylight and improve well-being and performance

Blog modulaire lichtstraten

A considerable body of research shows that people prefer daylit spaces to those lacking natural light. Why should this be? If there is sufficient light to see, why would people prefer one source to another? To answer this question, we need to understand the evolved relationship between humans and natural light

Over the last one and a half centuries, artificial light and the restructuring of working times have seemingly ‘liberated’ us from the diurnal cycles of light and dark that nature imparts on us. Yet recent research has shown that this separation from nature comes at a considerable cost, causing health and social problems. A reconnection to the rhythms of nature is therefore needed – and this will also have a profound influence on architecture.

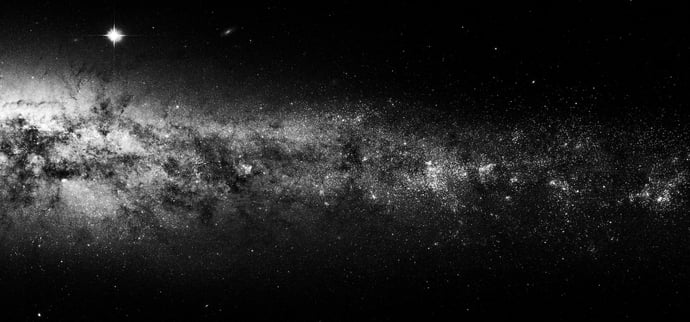

When viewing the night sky, most of us feel an intimate connection to the universe. Yet starry skies and moonlit nights have become increasingly rare for city-dwellers today. Given the harm that too much light at night is inflicting on human beings and ecosystems, it is time to reconsider our relationship to the ‘nocturnal side’ of our lives and our culture.

While the science of well-being is relatively nascent, the UK Government’s ‘Foresight’ project sheds a great deal of light on five factors that have a proven effect on well-being1, leading to the definition of the Five Ways to Well-Being (connect, keep active, take notice, keep learning, give).2 The question remains, though, how do we design buildings that can positively influence these five factors?

To truly enhance human well-being, building design needs to move beyond optimising single parameters such as temperature and humidity, to more holistic approaches that take their cues in health-supporting human behaviours. Based on the Five Ways to Well-Being that have recently been established by scientists, this article outlines the way architects can consider these aspects in their designs, in order to nudge building users into a healthier way of living.

How do you design and operate a healthy building? Answers to these questions can be found in an increasing number of methodologies and rating schemes that have seen the light around the world in recent years. They all share the ambition to strengthen the health and well-being of building users. Yet, they vary widely in terms of their overall scope, the metrics they use as proof of performance, and the weight that they put on the different phases in a building’s life cycle. The following chronological overview presents a selection of the most important and forward-looking tools, as well as their underlying methodologies.

De Hessenwald School in Weiterstadt, Duitsland, is een voorbeeld van energie-efficiënte, hedendaagse architectuur die een nieuw leer- en pedagogisch model faciliteert. Het goed verlichte en goed geventileerde atrium dat drie verdiepingen telt, staat centraal in zowel het model als het gebouw.

Ryparken Lille Skole (letterlijk 'Ryparken kleine school') is gevestigd in een oude textielfabriek in Kopenhagen. Jarenlang hadden de school en zijn gebruikers last van de vervallen staat van het gebouw. Tot begin 2010, toen het schoolbestuur besloot om een groot renovatieproject te beginnen.

In 2012 kwam er een einde aan tien jaar overleg, toen de lokale overheid een plan aannam om de oude school in Huddinge, Zweden te renoveren. De school uit 1961 was in de stijl van de jaren zestig gebouwd en was in goede staat.